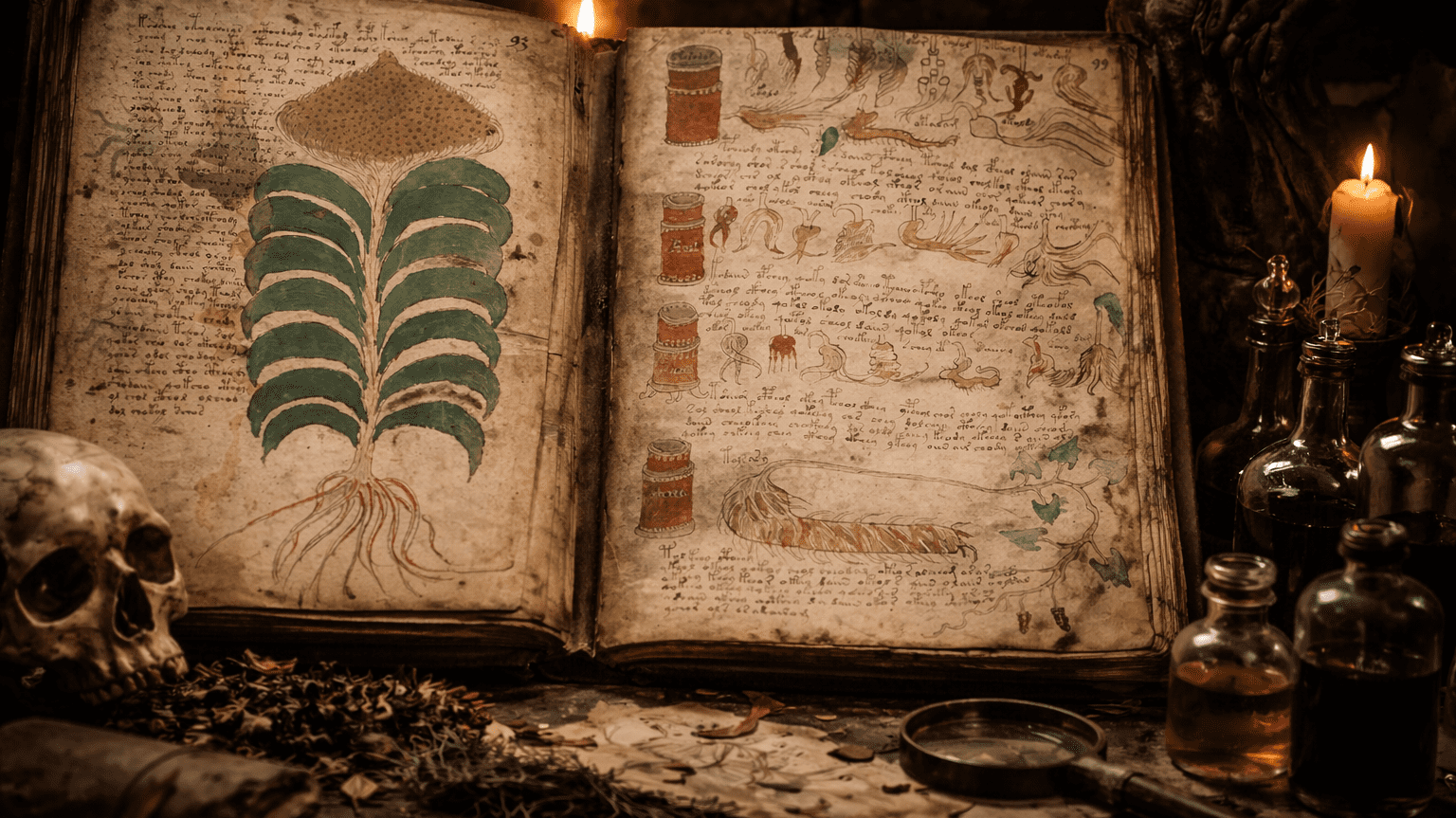

Imagine a book that no one in the world can read. For over a century, this single volume has stared back at the brightest minds in cryptography, linguistics, and history, refusing to give up its secrets. It is filled with illustrations of fantastical plants that do not exist on Earth, strange astronomical charts, and cryptic diagrams, all accompanied by a flowing, elegant script that belongs to no known language. This is the mystery of the Voynich manuscript, a 600 year old puzzle that has so far defeated every attempt to solve it. Housed safely at Yale University’s Beinecke Library, its 246 pages have been analyzed by supercomputers and scrutinized by scholars, yet its meaning remains completely hidden. The book, carbon dated to the early 15th century, between 1403 and 1438, has been called the world’s most mysterious manuscript, leading many to wonder if it is an elaborate, meaningless hoax. But a recent breakthrough suggests a far more intriguing possibility. The secret may not be in the language itself, but in the clever method used to conceal it.

A new study has shifted the focus from trying to decode the script, known as Voynichese, to understanding how it might have been created in the first place. The research, published in the esteemed journal Cryptologia, proposes that the entire manuscript could be a known European language, like Latin or Italian, disguised by a sophisticated encryption system, or cipher. This idea is not new, but what is remarkable is that the researchers have developed a working model of a cipher that can produce text that looks and behaves just like the script in the book. This newly devised system offers the most compelling explanation to date for how the enigmatic text was constructed. It suggests we are not looking at a lost language or nonsense, but a message that was deliberately and systematically hidden.

The proposed method is called the Naibbe cipher, named after a 14th century Italian card game. Developed by science journalist Michael Greshko, this system uses simple tools that would have been available to a 15th century scribe: playing cards and a die. The process is both random and structured. First, a familiar text in Latin or Italian is broken down into single and double letters using the roll of a die. Then, a playing card is drawn. This card directs the scribe to one of six different encryption tables, which are essentially charts that substitute the original letters with the strange glyphs of Voynichese. When this two step process is applied, the resulting text is eerily similar to that found in the medieval manuscript. It shares the same statistical patterns, such as how often certain symbols appear, the typical length of words, and even certain grammatical structures.

This discovery is significant because it provides the first fully documented method for converting a known language into a script that mimics the unique properties of Voynichese. While Greshko himself notes that the Naibbe cipher is almost certainly not the exact system used to write the manuscript, its success demonstrates that such a system was possible. It also elegantly solves another long standing puzzle within the manuscript itself. Handwriting analysis has identified at least two distinct styles of script, known as Voynich A and Voynich B, suggesting multiple authors. How could two different people collaborate on an unbreakable code? The Naibbe cipher provides a logical answer. Multiple scribes, working from the same set of rules involving cards, dice, and encryption tables, could produce text that was consistent in its underlying structure yet distinct in its personal style.

This new theory does not, of course, translate the Voynich manuscript. The door to its meaning remains locked. But the Naibbe cipher provides a potential keyhole, suggesting that the book is not an artistic fraud but a genuine piece of cryptography. It points future research away from the search for a new language and toward the methodical work of codebreaking, treating the text as an encrypted version of a familiar European tongue. The ancient volume continues to guard its secrets, but we are now closer than ever to understanding the ingenuity of the minds who created this beautiful and baffling work of art. This new perspective on the ancient puzzle comes from a study published in the journal Cryptologia, as reported by Archaeology Magazine.