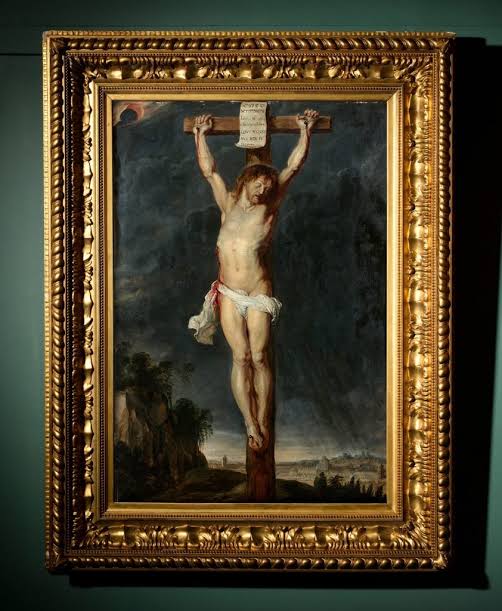

What hidden masterpieces are still lurking, waiting to be rediscovered, transforming our understanding of art and history? A shadow from the 17th century, a canvas consumed by time and rumour, recently stepped back into the light, confirming that the most thrilling chapters of art history are often those yet to be fully uncovered, proving the archives do not hold the final word on human creation. This dramatic reappearance of a long lost treasure—an authentic work by the towering figure of Flemish Baroque, Sir Peter Paul Rubens—sent an electric charge through the otherwise sedate halls of academic art history and the volatile global art market. The painting, whose existence was previously confined to obscure archival mentions and perhaps faded sketches in forgotten journals, surfaced unexpectedly in France. Its culmination in a high stakes auction, where it ultimately fetched nearly three million euros, vastly exceeding all initial estimates, was not just a successful sale; it was the resurrection of a foundational piece of Western visual culture, a physical, vibrant link to one of the most prolific, sophisticated, and influential workshops in the history of art.

Rubens was more than just an artist; he was a diplomat, a scholar, and an artistic industrialist whose pervasive influence spans centuries, shaping everything from portraiture to religious history painting. Due to the enormous demand for his work and his large, highly organized studio, many pieces were copied by assistants, adapted by students, or simply vanished into the depths of European private collections over the centuries, making any verified, authenticated rediscovery a profoundly rare and intensely valuable event. The stakes involved in confirming this specific painting were monumental: authentication would require rewriting catalogue raisonnés, adjusting valuation standards across the entire Baroque spectrum, and offering a new lens through which to view a specific period of the master’s life. Failure to confirm its authenticity, conversely, would relegate it to a mere footnote in an auction house report, diminishing its financial and historical worth instantly. The weight of four centuries of history rested on the meticulous efforts of a small group of conservators and scholars tasked with peeling back the veil of time.

But how, in the modern era, does one definitively confirm that a piece of timber and pigment, hidden away in relative obscurity for generations, is truly the undisputed handiwork of a titan like Rubens, whose style was so widely imitated? The initial excitement that greeted the painting’s emergence was necessarily tempered by profound, academic scepticism. Historical precedent shows that many declared “lost” masterpieces turn out to be excellent, contemporary student copies, or sophisticated later period homages, painted perhaps centuries after the master’s death. To the untrained, or even the moderately trained eye, the composition might powerfully echo the energetic drama and muscular movement that characterize Rubens, but the unforgiving world of high art demands undeniable scientific proof, not just aesthetic intuition. The authentication process thus became a complex, multi layered forensic investigation that required the most sophisticated technological arsenal available, pushing the very boundaries of conservation science and historical detective work, seeking that unique, irreversible signature hidden within the very physical structure of the canvas. The investigative team faced countless hours in the sterile confines of the lab, carefully peeling back layers of accumulated dirt, discolored varnish, and previous, often clumsy, restoration attempts, hunting for a specific pigment mix, an idiosyncratic brushstroke pattern, or a detail of preparation that was singularly and uniquely the master’s own creation. Could they truly isolate the individual fingerprint of a 17th century icon, separated from us by the vast chasm of time?

The methodology deployed began with infrared reflectography, perhaps the most revealing tool in the art historian’s arsenal, a technique that allows experts to peer physically beneath the visible paint layers to observe the *underdrawing* or preparatory sketch. This initial roadmap, often quickly executed in charcoal or chalk, reveals the artist’s first thoughts, his spontaneous corrections, and the crucial compositional decisions that define an original work’s creation. Rubens had a very specific, confident, and almost electric style of underdrawing that differed dramatically from his pupils. Simultaneously, high resolution X ray imaging was deployed, capitalizing on the principle that X rays penetrate paint layers differently based on the density of heavy metal pigments used. Lead white, a universally common 17th century ground pigment, appears strongly in the resulting X radiograph, and the image can reveal subtle *pentimenti*—those tiny, often invisible changes the artist made during the active painting process, such as shifting a figure’s head slightly or rearranging a fold of drapery. These artistic second thoughts are crucial because they capture the creative struggle and moment of design revision, something that is almost universally absent in copies, as a copyist merely replicates the finished image. Finally, the microscopic analysis of pigment particles, specifically employing non destructive techniques like X ray fluorescence spectrometry, was essential. This method determines the precise elemental composition of the pigments. Rubens’s Antwerp workshop was known to have employed specific, sometimes rare, and geographically sourced pigments characteristic of the Netherlands during the early 1600s. The presence of certain trace elements in the lead, or the precise chemical ratios in the earth tones, acted as an irrefutable chronological and geographical stamp, confirming the piece aligned perfectly with the known materials and practices available to the master himself during that exact period.

After weeks of sustained, intense scrutiny—comparing the discovered pentimenti to known, verified Rubens works, matching the distinct spontaneity of the underdrawing, and confirming the precise chemical signature of the pigments—the verdict was rendered definitive and unanimous. The long lost canvas was, unequivocally, a genuine Rubens, rescued from the oblivion of history. This meticulous scientific and historical confirmation did far more than merely justify the spectacular auction price; it powerfully illuminated a previously obscure corner of the master’s vast output. Art historians can now place the work precisely within his complex timeline, gaining a deeper understanding of the developmental trajectory of his style during a critical moment in his career. It offers profound, fresh insights into his specific technique, the operational dynamics of his collaborators, and the identity of the significant patrons he served. The fact that the painting was sold for a staggering sum approaching three million euros, utterly dwarfing the conservative initial estimate of a mere few hundred thousand, serves as the most powerful testament to the financial and cultural gravity that such a rigorous historical and scientific affirmation carries. The incredible rediscovery transforms a dusty, long forgotten object into a truly vital, living historical document, now ready to be studied, exhibited, and celebrated by millions worldwide who might otherwise never have known of its quiet, centuries long exile. The canvas is once again a radiant presence, a voice echoing across four centuries, reminding us that true history is not a static, finished text locked away in archives, but a dynamic, unfolding, tangible narrative constantly being revised by the objects that emerge, almost miraculously, from the shadows of time, demonstrating the enduring, profound power of great art to transcend time and reclaim its rightful, luminous place in the human story.